Join me, a former engineer and patent attorney, in exploring how people intersect with Technology and Science.

To illustrate the wide breadth of topics found in Trials By Technology, or TBT, we shift from Earthbound stories about the social structure of honeybees and the efficient squeezing of waste from our food distribution to space exploration.

Well before Elon Musk and Space X launched a Tesla (batteries apparently included) into orbit, there was another launched electric vehicle. Unlike the Tesla launch which was strictly a publicity stunt, the Lunar Rover Vehicle, or LRV, was the real deal in extraterrestrial transportation. Batteries definitely included, the LRV, an edition so limited only a handful or two were manufactured, ferried people on the surface of the Moon, the most inhospitable, most rugged surface ever traversed.

As Earl Swift details for us in Across the Airless Wilds, it was a heck of a ride.

Designing equipment to operate in space is one of the most challenging tasks ever. Reliability is a must. Any breakdown could prove lethal if the astronauts couldn’t make it back to the Lunar Landing Module before their air ran out.

There is the big temperature difference: in space, temps range from toasty in sunlight to abysmally cold in the shadows. Metals and nonmetals alike expand and contract. There is the vacuum of space, where any liquids must be sealed and solids tested to ensure no offgassing or sublimation. And there is solar radiation which can play havoc with electronics and people alike.

Swift ventured to see an actual LRV at the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama. I once worked in Huntsville, at Redstone Arsenal. I loved the place for its pine forests, its north-south line of hills to the east and its friendly people.

Swift walked the length of the Saturn V, laid on its side, marveling at the giganticness of the rocket. As he and his guide came to the LRV, the guide asked Swift what he thought:

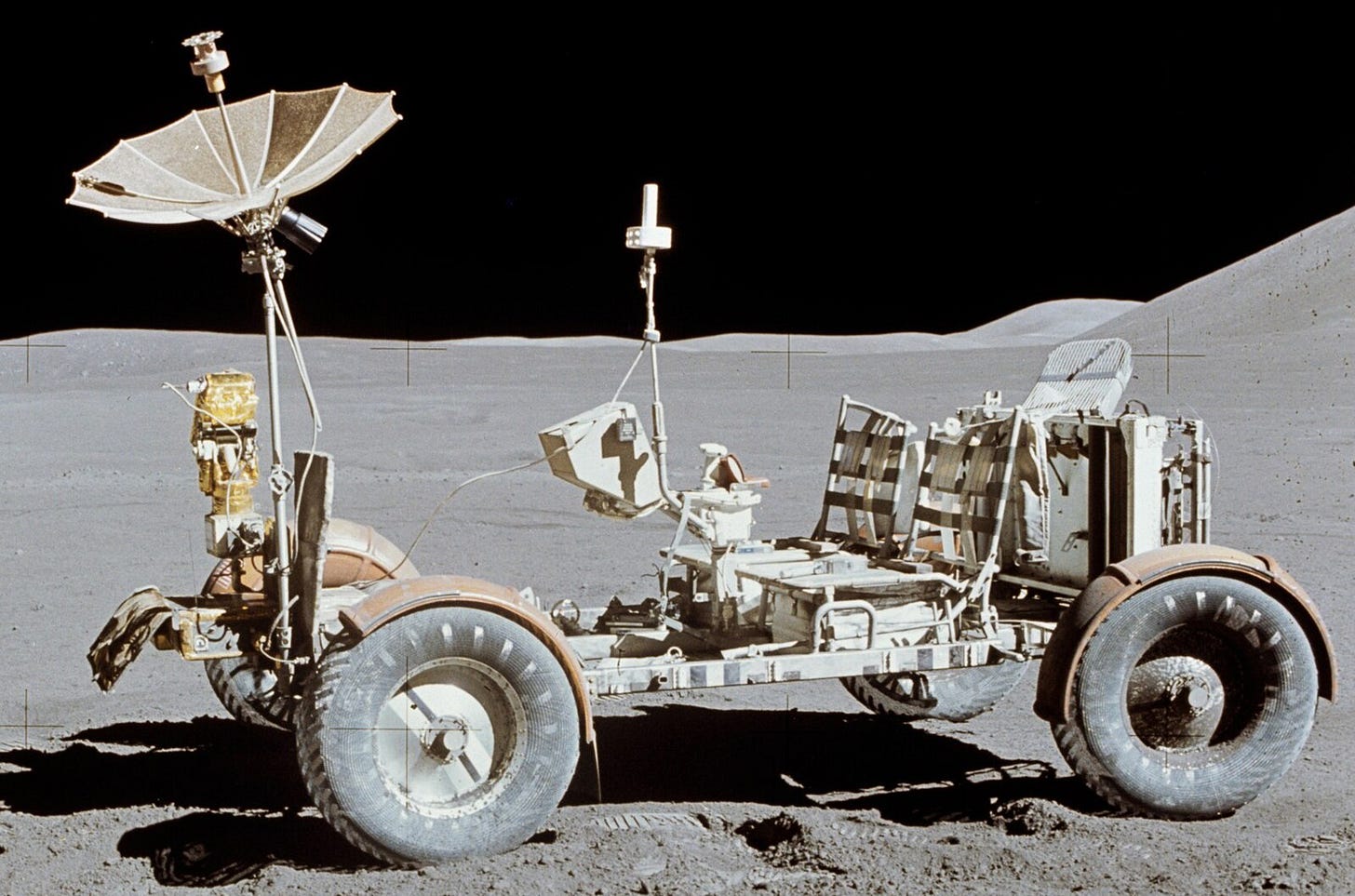

What I thought was that it looked just as I’d imagined it. All business. Built with the precision and purpose of Apollo machinery. A wondrous meld of engineering and imagination, deceptively simple, conceived at a time when the available tools to work out its hidden complexities were slide rules, blackboards, and hand-drawn blueprints . . .

Add extensive testing to the list. Build and test it under as many conditions as you can think of. Today, tools such as CAD and modeling software save time and money in design and testing. But the tools available back then were far less sophisticated than now.

Swift goes on describing the creative process in a way anyone, engineers or the very curious can appreciate:

. . . Its builders distilled everything essential to an earth-bound off-roader to its indivisible minimum, its smallest and lightest and most fundamental iteration, then whittled even further. On Earth, it weighed 460-odd pounds—not much more than a single astronaut in his space suit—but on the lunar surface weighed a sixth as much, thanks to the moon’s weaker gravity. So it was that the four electric motors turning its wheels together churned out just one horsepower. You can buy a gutsier shop vac, but at less than eighty lunar pounds, that’s all the punch it needed.

A one-horse buggy, absolutely astounding! This thing was exotically built for its specific environment:

On the job, it proved sturdy enough to shrug off a lot of abuse. Yet the museum’s example rested on a display stand that propped up its aluminum frame; without it, the chassis might have sagged under the pull of the Earth’s gravity by now. If I were to step onto the floorboard, I’d snap it. I focused on its tires, which I’d long admired in pictures. They were the shape and size of all-season radials, only made of stainless steel mesh. They supported the rover on the moon, but here, minus the stand, would squash flat. Each, rim included, weighed just twelve Earth pounds.

Seating consisted of straps slung on aluminum frames that had to accommodate the astronauts’ backpacks. I’ve got to get back to Huntsville and see this thing.

Swift deftly points out why NASA expended so much in engineering and money developing the vehicle when only a few were actually built. During Apollo 14 which flew in 1971 and landed without a rover, astronauts Alan Shepard and Edgar Mitchell walked on foot pulling an equipment cart, intending to explore inside of a crater not far from their landing site. They were excited to be the first to take rock samples from inside a crater. Walking on the moon is vastly different than on Earth, due to the disorienting effects of the shorter horizon, the black sky, the grayness of the lunar regolith, among other things. They struggled to climb the slope under unfamiliar conditions, using up their precious air supply before attaining the crater rim.

Determined to push on, they requested and received permission from Mission Control in Houston to extend their moonwalk, digging deeper into their critical air reserves so they could range further and still return safely to the moon lander. They never reached the crater interior. Later they learned they had hiked to within sixty-five feet of the crater rim.

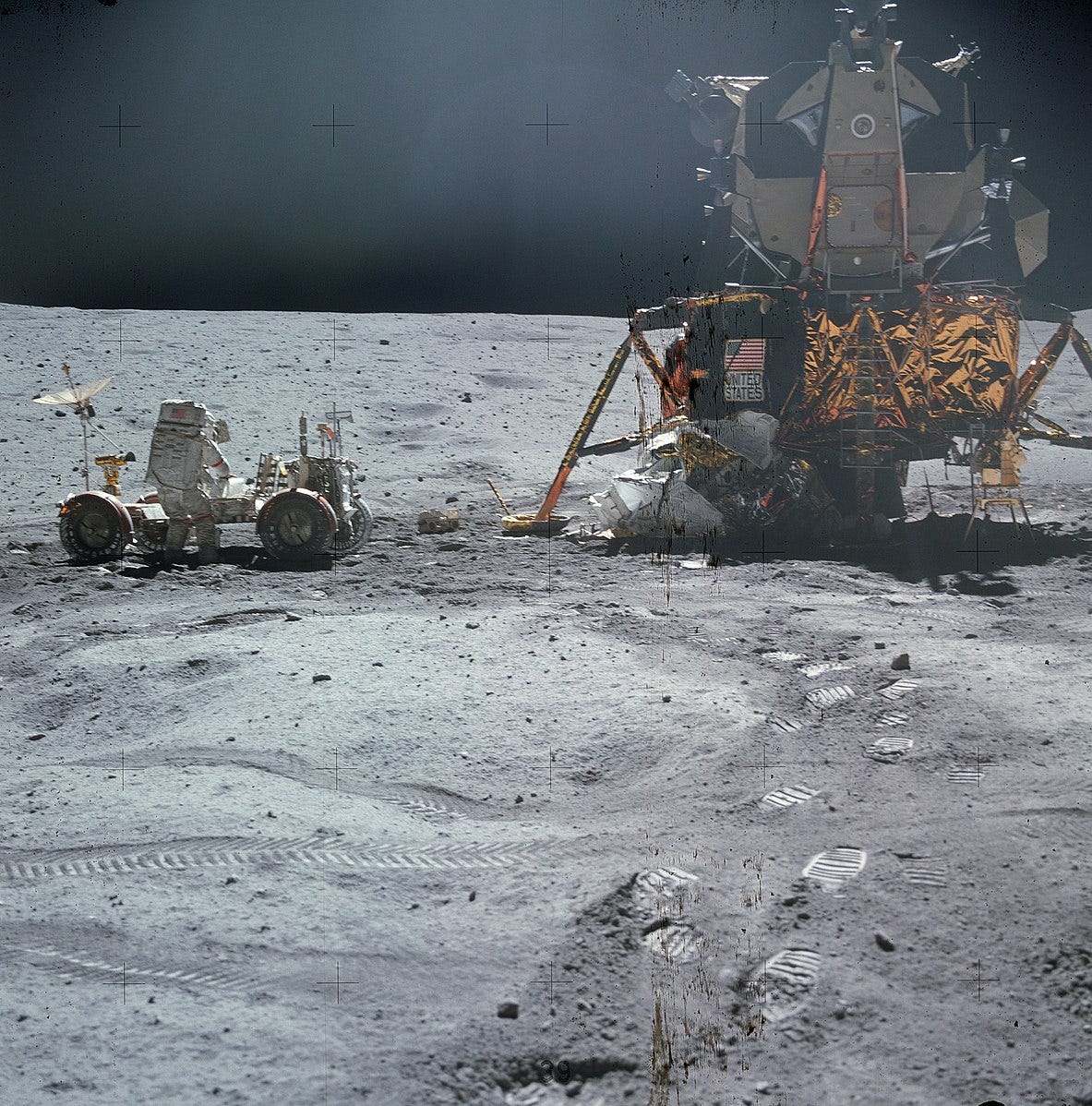

The LRVs accompanied Apollos 15, 16 and 17, each making the one-way trip, vehicle return not part of the rental agreement. The picture above illustrates the delicate folding and stowing of the vehicle into the lunar lander. The LRVs brought moon exploration out of pioneer days of pulling carts to modern ranging. Sitting on the lawn-type chairs, strapped in, pushing a joystick to roll forward, stop, turn, the rovers didn’t travel fast, but they operated reliably as intended on the harshest surface environment humankind has ever encountered.

Fifty plus years later, even though we have Earth-bound electric vehicles with better and more sophisticated electronics, more compact and powerful electric motors, the lunar rovers are unmatched in exploration transportation.

I want to drive one.

All the Best,

Geoff

If you enjoyed this post, please hit the heart “❤️” so others can find it. It’s at the bottom and at the top.

Thanks for reading Geoff’s Substack! Subscribe for free to receive new posts and support my work.

Really cool story. Some new information for me. Still amazing at what they accomplished with the available technology.

In considering the lackluster performance of our current cell phones, I'm still mystified at how that red phone land line in the Oval Office was able to speak to these astronauts in real time.